英研究称5亿年前生物DNA错误复制促成人类

英研究称5亿年前生物DNA错误复制促成人类

2012/07/30 17:14:39

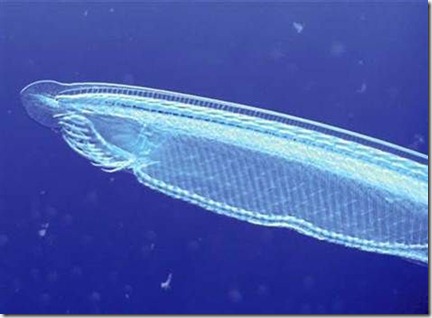

一条文昌鱼,它是人类和其它有脊椎动物的远古近亲。它似乎和一种早期无脊椎生物在它发生那两次严重的基因复制错误之前的状态相当相似

北京时间7月27日消息,据国外媒体报道,一项最新研究向我们讲述了这样一个故事:在大约5亿年前,在海底有一条无脊椎生物经历了两次成功的DNA复制——这是一次“程序错误”,但是这一个“错误”却意外地触发了其它生物包括人类的最终出现。

好消息是这一次古老的基因“突变”极大地改善了细胞通讯系统,因此我们的身体细胞整合信息的能力比现有最先进的智能手机还要好。不过也有坏消息,那就是这种信息通讯偶尔会出现崩溃,导致这一现象的基因渊源最早可以追溯到寒武纪时期,这一缺陷会导致糖尿病,癌症和神经错乱。有关这一研究的论文作者之一,英国邓迪大学生命科学学院的卡罗尔·麦肯托什教授(Carol MacKintosh)表示:“借由有性生殖的生命体一般拥有两份基因,分别遗传自父方和母方。而在5亿年前所发生的事情便是:这一过程在一只无脊椎动物的身上出现了错误,它继承了两次原本应当只继承一次的基因组。而在后来的几代中,这一错误反复发生,基因数量再次翻倍。”

麦肯托什教授表示,这样的基因复制现象也同样存在于植物演化过程中。因为采用这种新方法繁殖的后代在自然界中的适应和生存能力显然更强。她说:“这种复制并非是稳定的,然而绝大部分被复制的基因都很快丢失了,远远早于人类出现之前。”但是麦肯托什教授和她的小组发现确实有一小部分幸存了下来。

她的研究组对人体细胞内数百种不同的蛋白质进行研究,考察它们对生长因素和胰岛素的反应情况,胰岛素是荷尔蒙的一种。在这一过程中涉及的关键性蛋白质被称作14-3-3。在这项最近的研究工作中,科学家们对这些蛋白质进行制图,分类并展开生物化学分析。正是在这一过程中她们回溯到了最初的基因复制时期,回溯到了寒武纪。

世界上最初携带这一基因组的生物究竟是什么目前仍然无从知晓,不过麦肯托什教授表示现代生活在海中的文昌鱼似乎和这种早期无脊椎生物在它发生那两次严重的基因复制错误之前的状态相当相似。因此,麦肯托什教授认为“文昌鱼可以被视作是今天所有脊椎动物的非常古老的姐妹。”

这种被一路继承下来的蛋白质似乎已经经过演化,它会形成一个“小组”,相比单个蛋白质的情况,这种蛋白质组能生成更多的生长因子。麦肯托什教授表示:“因此在人体细胞内部的这一系统的行为就像是一套信号多路分发系统,就像是我们的手机能得以同时处理多条信息的功能类似。”

尽管像这样的“团队合作”有时也并非一直是有益的。但是研究人员们指出如果某项关键性的功能是由单一一个蛋白质实现的,比就像是在文昌鱼体内那样,那么这一蛋白质的丢失或突变将会是致命的。而如果蛋白质进行“团队工作”,即便其中的一个或几个出现丢失或变异,这个个体也将得以存活下来,尽管可能会有一些身体功能上的障碍。这种缺陷或缺陷可以解释疾病的发生,如糖尿病,癌症这些让人类深受其苦的病症。

麦肯托什教授说:“在二型糖尿病中,作为对胰岛素的反应,肌肉细胞失去了吸收糖的能力。与此相反,癌细胞则是贪得无厌,完全打破规则,肆意抢占其它细胞的营养,疯狂生长。”克里斯·马歇尔(Chris Marshall)是英国皇家癌症医院所属癌症研究中心的细胞生物学教授。他说他认为这项研究工作“加深了人们对于控制我们细胞行为的信号机制演化进程。”

麦肯托什教授和她的同事们目前正将注意力集中在一种能引起黑色素瘤和神经错乱的蛋白质大类上。由于这项研究中可能牵涉到和远古时期基因突变事件之间的联系,这项研究在帮助对抗疾病的同时还将有望揭开人类和其它动物的演化之谜。

Translation from ScienceNet

Ancient ‘mistake’ led to humans

Jennifer Viegas

More than 500 million years ago a spineless ocean-dwelling creature experienced a dramatic change to its DNA, which may have led to the evolution of vertebrates, says a new study.

The good news is that these ancient DNA doublings boosted cellular communication systems, so that our body’s cells are now better at integrating information than even the smartest smartphones.

The bad part is that communication breakdowns, traced back to the very same genome duplications of the Cambrian Period, can cause diabetes, cancer and neurological disorders.

“Organisms that reproduce sexually usually have two copies of their entire genome, one inherited from each of the two parents,” says Professor Carol MacKintosh, co-author of a study appearing today in the Royal Society journal Open Biology.

“What happened over 500 million years ago is that this process ‘went wrong’ in an invertebrate animal, which somehow inherited twice the usual number of genes. In a later generation, the fault recurred, doubling the number of copies of each gene once again.”

MacKintosh, of the College of Life Sciences at the University of Dundee, says such duplications also happened in plant evolution. As for the progeny of the newly formed animal, they remarkably survived and thrived.

“The duplications were not stable, however, and most of the resulting gene duplicates were lost quickly - long before humans evolved,” she says. But some did survive, as MacKintosh and her team discovered.

Her research group studies a network of several hundred proteins that work inside human cells to coordinate their responses to growth factors and to insulin, a hormone. Key proteins involved in this process are called 14-3-3.

Cambrian ancestor

For this latest study, the scientists mapped, classified and conducted a biochemical analysis of the proteins. This found that they date back to the genome duplications, which occurred during the Cambrian.

The first animal to carry them remains unknown, but gene sequencing shows that a modern day invertebrate known as amphioxus “is most similar to the original spineless creature before the two rounds of whole genome duplication,” says MacKintosh. “Amphioxus can therefore be regarded as a ‘very distant cousin’ to all the vertebrate (backboned) species.”

The inherited proteins appear to have evolved to make a “team” that can tune into more growth factor instructions than would be possible with a single protein.

“These systems inside human cells therefore behave like the signal multiplexing systems that enable our smartphones to pick up multiple messages,” says MacKintosh.

The downside of multiplexing

The teamwork may not always be a good thing, though. The researchers propose that if a critical function were performed by a single protein, as in amphioxus, then its loss or mutation would likely be lethal, resulting in no disease.

If multiple proteins are working as a team, however, and one or more becomes lost or mutated, the individual may survive, but could still wind up with a debilitating disorder and pass it onto the next generation. Such breakdowns could help to explain how diseases, such as diabetes and cancer, are so entrenched in humans.

“In type 2 diabetes, muscle cells lose their ability to absorb sugars in response to insulin,” says MacKintosh. “In contrast, greedy cancer cells don’t await instructions, but scavenge nutrients and grow out of control.”

Chris Marshall, a professor of cell biology at the Institute of Cancer Research at Royal Cancer Hospital, thinks the research “gives new insights into the evolution of signalling mechanisms that control cell behaviour.”

MacKintosh and her team are now focusing on the protein families whose upset causes melanoma and neurological disorders. Because of the likely connection to ancient genetic events, the research could shed light on human and other animal evolution while also helping to unravel diseases.

Orignal TEXT from ABCsicence