染色体免疫共沉淀ChIP方法程序

染色体免疫共沉淀ChIP方法程序

2010/08/17 08:23:25

ChIP方法程序(一)

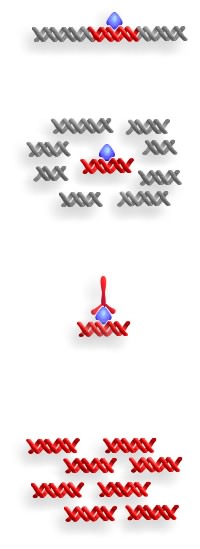

染色体免疫共沉淀(Chromatin immunoprecipitation,ChIP)是一种可在体内用来确定与某一特定蛋白结合或蛋白定位所在的特异性DNA序列的技术。方法程序如下图:

第一步:用甲醛在体内将DNA结合蛋白与DNA交联(DNA-binding proteins are crosslinked to DNA with formaldehyde in vivo.)

第二步:分离染色体(质),剪切后的DNA小片段与结合蛋白结合(Isolate the chromatin. Shear DNA along with bound proteins into small fragments.)

第三步:用特异性抗体与DAN结合蛋白结合,用沉淀法分离复合体。反向交联操作释放出DNA,并消化蛋白质(Bind antibodies specific to the DNA-binding protein to isolate the complex by precipitation. Reverse the cross-linking to release the DNA and digest the proteins.)

第四步:用PCR扩增特异DNA序列,以确定是否与抗体共沉淀(Use PCR to amplify specific DNA sequences to see if they were precipitated with the antibody.)

ChIP方法程序(二)

染色体免疫共沉淀(Chromatin immunoprecipitation,ChIP)是理解染色体(质)的一种革命性工具,它能使我们了解染色体(质)及其相结合的因子之间的时空动态和相互作用。无论是考察单个启动子在很短时间内的变化,还是在整个人类基因组中考察某个转录因子,染色体免疫共沉淀技术都能使我们了解在自然状态下基因是如何被调控的。(Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) is a tool that has revolutionized our understanding of chromatin. ChIP has allowed us to dissect the spatio-temporal dynamics and interactions of chromatin and its associated factors (see Figure 1 for the structure of chromatin). Whether looking at minute-by-minute changes at a single promoter, or a single transcription factor over the entire human genome, ChIP has given us significant insight into how genes are regulated in their natural context.)

一、什么是ChIP?

ChIP的原理很简单:选择性富集包含某一特异性抗原的染色体(质)片段。能够识别某一蛋白或目的修饰蛋白的抗体被用来确定抗原在基因组中一处或多处的相对丰度。

ChIP包括以下几个步骤:

-

分离总染色体(质)(需要通过交联使目的抗原固定在染色体(质)与其结合的部位)。

-

将染色体(质)切割成片段(以提高精度)。

-

对切成片段的染色体(质)进行免疫沉淀。

-

免疫沉淀的染色体(质)片段进行分析,确定靶DNA序列水平与其输入的染色体(质)的相对丰度。

最后一步通常用PCR或基于杂交的分析技术。Allis和Wu(2004)已进行综述。

Allis, C.D. and Wu, C. 2003. Chromatin and chromatin remodeling enzymes, Part A, Vol. 375. Academic Press.

染色体免疫共沉淀(Chromatin immunoprecipitation,ChIP)方法程序

1. What is ChIP?

The principle of ChIP is simple: the selective enrichment of a chromatin fraction containing a specific antigen. Antibodies that recognise a protein or protein modification of interest can be used to determine the relative abundance of that antigen at one or more locations in the genome.

ChIP consists of the following steps (summarised in Figure 2):

-

Isolation of total chromatin (which may require cross-linking to fix the antigen of interest to its chromatin binding site)

-

Fragmentation of the chromatin (to achieve resolution)

-

Immunoprecipitation of the resulting chromatin fragments

-

Analysis of the immunoprecipitated fraction to determine the level of a target DNA sequence (or sequences) relative to its abundance in the input chromatin.

The final analysis is typically carried out using PCR or hybridisation-based techniques. A comprehensive review of the procedures and methodologies of ChIP can be found in Allis & Wu (2004).

Allis, C.D. and Wu, C. 2003. Chromatin and chromatin remodeling enzymes, Part A, Vol. 375. Academic Press.

Figure 1: The Structure of Chromatin

2. The original ChIPs

The overall methodology now referred to as ChIP has been continually refined since the seminal publications in the 1980’s by Gilmour and colleagues. They demonstrated an association of RNA polymerase II and topoisomerase I with active genes in Drosophila cells (Gilmour and Lis, 1985; Gilmour et al., 1986).

The first account of an antibody against a histone modification being used in ChIP was in 1988 by Hebbes et al. An antibody recognising N-acetyl-lysine was used to immunoprecipitate nucleosomes containing acetylated histones from 15-day-old chicken erythrocyte nuclei. The precipitated chromatin was then probed with (ß-globin and ovalbumin DNA sequences. Specific enrichment of the (ß-globin locus, but not the ovalbumin gene, demonstrated a link between histone acetylation and an active transcriptional state in vivo (Hebbes et al., 1988).

3. ChIP experiments: factors for consideration

3.1 The antibody

For a successful ChIP experiment the choice of antibody is paramount. Typically, ChIP’ing antibodies recognise histones, histone modifications or chromatin-associated factors. The specificity of each antibody needs to be well characterized; antibodies should be tested in both ELISA and Western blot (using target and non-target antigens as competitors) to confirm specific epitope recognition. Western blotting can be used to demonstrate that the correct target has been successfully immunoprecipitated.

Antibodies that recognise multiple antigens in the chromatin fraction should be avoided (or at least this should be considered in the final interpretation). Immunofluorescence can also be used to check that antigen recognition occurs in a more natural context, and can also be combined with competition assays.

Perhaps the most stringent test of a ChIP’ing antibody is to perform parallel ChIPs in wild type and mutant backgrounds to demonstrate that the observed enrichment is due solely to the target antigen.

Finally, the quantity of antibody, and the conditions under which to use it, should be determined empirically for each antibody. Typical starting IP conditions would be 2-5µg of antibody per 50µg of DNA (where the concentration of DNA has been measured in a deproteinized aliquot of the chromatin fraction).

Figure 2: Chromatin Immunoprecipitation - the steps

3.2 The Chromatin

Chromatin from most sources, including tissue, is a suitable substrate for ChIP. While the isolation procedure necessarily varies depending on the source, two types of ChIP can be recognised: Native and Cross-linked, known as NChIP and XChIP respectively.

(i) NChIP: Native chromatin is used as substrate. The advantage of this procedure over XChIP is that antigens cannot be obscured or modified by the chemical cross-linking. However, this lack of cross-linking necessarily means that only proteins very tightly associated with the chromatin can be immunoprecipitated, typically limiting this type of ChIP to histones and their modifications (O’Neill and Turner, 2003).

(ii) XChIP: Cross-linked chromatin is used as substrate. XChIP is more widely used than NChIP since it allows analysis of a much broader range of chromatin-associated factors (through physical cross-linking of weakly associated proteins). However, some antigens may prove difficult to immunoprecipitate with XChIP; changes to the epitope or occlusion may occur in the cross-linking process. The use of rapid cross-linking has been successfully used to follow temporal changes in chromatin, such as histone modifications (Orlando, 2000). Cross-linking is typically achieved using formaldehyde or UV treatment.

After purification, the native or cross-linked chromatin is digested, typically by micrococcal endonuclease, or mechanically sheered by sonication to generate chromatin fragments. Empirical manipulation of either of these processes can be used to generate a range of fragment sizes. Although this fragmentation gives sufficient resolution for most experiments, fragments of a specific size can be further purified if required (e.g. by sucrose gradient centrifugation). In this way pure mononucleosomes can be analysed.

4. Flavours of ChIP

The conceptual limitations of ChIP analysis are only the antigens that can be targeted, and the ways in which associated DNA can be analysed. Novel techniques continue to be published.

4.1 Temporal ChIP

Chromatin can be analysed at multiple time points in response to specific signals. Although fixation times typically extend up to 15 minutes in duration, significant changes have recently been described between one-minute time points using this technique (Metivier et al., 2003).

4.2 ChIP on DNA micro-arrays (ChIP on chip)

Combining ChIP and micro-array technology allows genome-wide analysis of antigen distribution. Immunoprecipitated chromatin is quantitatively amplified and labelled using random primers, then used to probe an appropriate DNA microchip. In this way, given efficient precipitation and a comprehensive array, a complete genome localisation map for the protein or modification of interest can be assembled (Bernstein et al., 2002; Kurdistani et al., 2002).

4.3 Re-ChIP

As the name suggests two sequential immunoprecipitations are performed with two different antibodies. Successful re-ChIP identifies two targeted antigens as occurring together on the same chromatin fragments. This data may be used to assemble the proteins into higher order complexes. However, care must be taken not to over-interpret such information; it is possible to envisage two antigens occurring consistently in close proximity at a given sequence without existing in the same complex (Metivier et al., 2003).

4.4 ChIP Chop

Specific immunoprecipitation of methylated DNA itself has proved problematic; the available antibodies against 5-methyl-cytosine do not seem to immunoprecipitate methylated DNA. To overcome this problem, post-ChIP hydrolysis (‘chopping’) of DNA that is methylated at multiple purine-cytosine sites is performed using an enzyme called McrBC. Fragmentation within the target sequence prevents PCR amplification. With this technique it is possible to determine whether the DNA associated with a particular antigen is heavily methylated or not (Lawrence, 2004).

5. Quantification

Although hybridization using labelled probe sequences is still used to detect targets in the precipitated chromatin, PCR based methods are now more commonly used. Standard PCR can be used, but Real Time PCR (RT-PCR) is emerging as the method of choice due to its demonstrably quantitative nature, inbuilt controls for multiple product generation, and compatibility with TaqMan® and other stringent probe technologies. A typical set-up might use TaqMan® probe and/or Sybr Green technologies® to detect reactions carried out in an RT-PCR instrument such as the ABI 7000 according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

6. Analysis

Enrichment of a target is not solely dependent on the quantity of antigen associated with it. Precipitation will be affected by the accessibility of that antigen in that particular chromatin environment, the affinity of the antibody and the precise conditions of the immunoprecipitation. For this reason, the level of enrichment is always expressed as a ratio of bound (or precipitated) sequence over input. This also means that absolute levels of different antigens present at the same sequence cannot be directly compared. An example of an actual ChIP experiment is shown in figure 3.

Figure 3: Example of a result from a ChIP experiment

7. Protocols

A large number of protocols for ChIP have been published. We have included protocols from well respected researchers for chromatin preparation, NChIP and XChIP within the Abcam Chromatin and Gene Regulation webpage.

References:

C. D. Allis & C. Wu (Eds). (2004) “Chromatin and chromatin remodelling enzymes”, Methods in Enzymology v376, Elsevier Academic Press 2004.

Bernstein, B. E., Humphrey, E. L., Erlich, R. L., Schneider, R., Bouman, P., Liu, J. S., Kouzarides, T., and Schreiber, S. L. (2002). Methylation of histone H3 Lys 4 in coding regions of active genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99, 8695-8700.

Gilmour, D. S., and Lis, J. T. (1985). In vivo interactions of RNA polymerase II with genes of Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Cell Biol 5, 2009-2018.

Gilmour, D. S., Pflugfelder, G., Wang, J. C., and Lis, J. T. (1986). Topoisomerase I interacts with transcribed regions in Drosophila cells. Cell 44, 401-407.

Hebbes, T. R., Thorne, A. W., and Crane-Robinson, C. (1988). A direct link between core histone acetylation and transcriptionally active chromatin. Embo J 7, 1395-1402.

Kurdistani, S. K., Robyr, D., Tavazoie, S., and Grunstein, M. (2002). Genome-wide binding map of the histone deacetylase Rpd3 in yeast. Nat Genet 31, 248-254.

Lawrence, R. J., Early, K., Pontes, K., Silva, M., Chen, Z. J., Neves, N., Viegas, W. & Pikaard, C. S. (2004). A concerted DNA methylation/histone methylation switch regulates fRNA gene dosage control and nucleolar dominance. Molecular Cell 13, 599-609.

Metivier, R., Penot, G., Hubner, M. R., Reid, G., Brand, H., Kos, M., and Gannon, F. (2003). Estrogen receptor-alpha directs ordered, cyclical, and combinatorial recruitment of cofactors on a natural target promoter. Cell 115, 751-763.